When you are ready to launch a new business or a new product, you know you need to put a lot of time and thought into what you call it.

Creating the right name tag can mean the difference between success and failure. Just think, no one was particularly interested in importing the Chinese gooseberry until the New Zealand produce company Turners and Growers renamed it the “kiwifruit” in 1959.

But some product names are such a good match that consumers start using the brand name for the product or service itself. Kleenex is one example. Although it is a registered trademark of Kimberly-Clark Corporation, Kleenex has become synonymous with “tissue.”

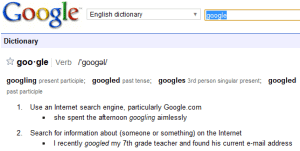

Google is another well-known victim of this so-called genericization. The Oxford dictionary added the verb “google,” meaning to search for something on the internet, in 2006.

Did you know that many everyday items, including zippers, kerosene, and windbreakers, were once trademarked brand names? The genericization of a brand name is a double-edged sword. On one side, have the satisfaction of knowing your brand is well-known and successful.

However, the downside is that you can experience brand dilution. Brand dilution occurs when the image of your product is weakened through overexposure or overuse. Some companies have lost the legal protection of their trademarked product name badges due to their widespread popularity.

Here is a list of 20 famous names that have become genericized.

- Jet Ski. Kawasaki Heavy Industries owns the rights to this name for a personal watercraft.

- Bubble Wrap. Sealed Air Corporation’s trademarked name for its cushiony packaging.

- Onesies. Gerber owns the rights to the name of their baby bodysuits.

- Jacuzzi. This company, which also makes faucets and toilets, is associated with its hot tubs.

- Crock-Pot. This company initially developed its slow cooker for beans.

- Escalator. The Otis company lost its trademark name for its moving stairway in 1950 in part because it has used the term in a generic way in its own marketing.

- Chapstick. Pfizer owns the rights to this brand name for its lip balm.

- Popsicle. The Unilever company says the generic term for their product is ice pop, freezer pop, or frozen pop.

- Q-Tips. I don’t know anyone who says cotton swabs, do you? But Unilever owns the Q-Tip brand today.

- Scotch Tape. The real Scotch “Magic Tape” is only made in Hutchinson, Minn. The other stuff you buy is simply adhesive tape.

- Sharpie. Permanent markers precede the Sharpie brand, but the name “Sharpie” has stuck in the consumer’s collective mind.

- Tupperware. This brand of storage containers got its name from Earle Silas Tupper, its creator.

- Velcro. You may see other brands of hook and loop fasteners, but the chances are good that you’ll call it Velcro. However, it is the trademarked name for Swiss electrical engineer George de Mestral’s invention.

- Weed Eater. Husqvarna Outdoor Products has the rights to this well-named gardening tool.

- Wite-Out. Bic says you should call a competitor’s product “correctional fluid.” The company also says the ingredients for this product are top-secret.

- Band-Aids. Do you ask for an adhesive bandage when you have a cut? I didn’t think so. Johnson & Johnson manufactures the “real” Band-Aids.

- Taser. TASER International holds the trademark for this electroshock weapon.

- Dumpster. The Dempster Brothers Inc. combined their name with the word “dump” to create the Dempster Dumpster brand.

- Xerox. Despite the Xerox company’s efforts to stop people from using their brand name as a substitute for the word “photocopying,” people still do it.

- Styrofoam. The Styrofoam name is a trademark of the Dow Chemical Company. It uses the foam material for insulation and water barriers, not plates, cups, or coolers.

This list is just the beginning. We could go on and on. So, what can you do to keep your brand name from becoming “generified?”

In an interview with Vox, creative strategist Rachel Bernard says, “I have a lot of clients that say, “I want to be Kleenex! I want to be Google!” But for every one of those, there are hundreds and hundreds that have actually lost their trademark.

‘”Trampoline” used to be somebody’s trademark, but through that process, they eventually lost it. It’s a cautionary tale that I have to tell lots of clients, but everybody is optimistic and thinks they’re going to be Google and not “trampoline.” It’s very hard to police consumer language.”